The government usually offers what it calls “unemployment insurance” for a person who loses his job. This can help with immediate bills, but the church needs to be ready to step in and help their members because it may be weeks before the money starts rolling in….

We have seen that during recessions, governments can be slow to respond to unemployment claims. The government response to the coronavirus pandemic proved how slow it can get. This story from the Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported that the jobless waited weeks to receive unemployment benefits in some cases:

The state Department of Labor processed 165,499 initial jobless claims last week, with many businesses continuing to lay off workers even as others reopen amid the coronavirus pandemic. More than 2 million claims seeking unemployment benefits have been handled since mid-March. While that includes duplicates, mistakes and some outright attempts at fraud, nearly half the claims have been judged as valid by authorities. “It is a massive task that we are undertaking right now,” said Mark Butler, state labor commissioner.

Starting in late March, that wave of claims overwhelmed a staff set up to handle a low-unemployment economy. Many thousands of jobless Georgians waited weeks for their application to be handled and for payments to start.

IT WAS EVEN WORSE IN NEW YORK

The New York Times interviewed a woman who represented the frustration of many, many filers who did not get immediate relief:

Seven weeks after she filed for unemployment benefits, Nadine Josephs was running out of money. The birthdays of her two teenage children loomed, and she was spending her days pleading for forbearance on overdue bills.

Holed up in her apartment in the East New York, Brooklyn, Ms. Josephs, 46, had grown increasingly frustrated since she filed her claim on March 16. And she was tired of hearing assurances from Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo to the thousands of desperate New Yorkers like her that the checks would be in the mail.

She had checked the mail, her email and her voice mail: No word from Albany in more than a month.

The article reports that she took an active approach trying to break through the system, such as calling the state Department of Labor, posting on Facebook, and even Tweeting to the governor.

There were similar reports from Texas:

Steven Parker, a welder in North Richland Hills, was one of the nearly 2 million Texans who filed for unemployment because of the pandemic.

Parker, 39, had already exhausted his 26 weeks of benefits in January after losing a job in August. He started a new job, only to lose that one as well in early April. Under the federal Pandemic Unemployment Emergency Compensation program, Parker was eligible for an additional 13 weeks of benefits, and the Workforce Commission approved his claim in April.

But more than a month later, Parker said he still hasn’t received any payments, and he can’t get through on the phone lines to ask what’s holding up the money. He’s getting desperate — he said he has burned through his savings and will run out of money before the end of the month.

“I just need something to keep things going, to put some gas in my car and food in my fridge,” Parker said. “You know it’s bad when you have to unplug your freezer.”

The Texas system was overwhelmed because the computer system was outdated:

The Texas Workforce Commission oversees workforce development, offering job training for Texans seeking employment and guidance for employers on running their businesses. And for out-of-work Texans, the agency processes unemployment claims and payments through its unemployment insurance system, which it built from the ground up in the 1990s because nothing like it was available from private vendors, Serna said…And when hundreds of thousands of Texans rushed to file for unemployment, those mainframes couldn’t handle the crushing demand.

CONCLUSION

For now, the state and federal governments, at least in Western nations, offer unemployment compensation for people who lose their jobs. The duration varies, but the benefits can last for up to 26 weeks or more. This increases during recessions because the politicians extend the program.

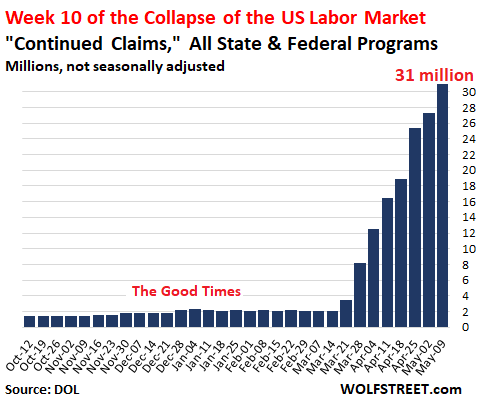

During the coronavirus recession that began in 2020, the number of jobless claims was historically unprecedented. The demand overwhelmed the outdated computer systems of many states. This chart from Wolfstreet shows how incredible the economic contraction was:

This slowed their processing time. Many people didn’t receive benefits immediately.

But they still had expenses like rent and utility bills to pay. And their savings were meager.

A church member who gets trapped by the delayed government response will have to turn to his church. The deacons should be ready to administer emergency relief.

One day, the welfare state governments of the world will exit the unemployment insurance business. This is because they will suffer severe economic sanctions for decades of unrestrained spending and debt accumulation represented by the off-budget, unfunded liabilities of programs like Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid.

The Great Default will force governments to stop funding many of its welfare programs. There will be outrage.

Churches must prepare for that day. Some churches and diaconates have already been tested by the coronavirus recession as a result of government failures on a small scale.